Driver Fatigue: Is it acceptable to drive when you are tired?

Fatigue has been reported to be four times more likely than drugs or alcohol to affect an individual’s ability to undertake their work and do it safely [1]. The Australian Transport Council has reported that fatigue contributes to 20-30% of all deaths on the road, which means it is as big a factor as speeding and drink driving [2]. The ability to monitor one’s fatigue has obvious implications for safety critical tasks in the workplace or in our community (e.g. driving a car).

Please complete our 4 question survey and click DONE before continuing.

Can we monitor our own fatigue?

Drivers who fall asleep at the wheel usually don’t remember actually falling asleep. As a driver cannot remain asleep for more than a few seconds without having an accident, this may account for why such recollection is poor in drivers who have been involved in an accident. They can however, often recall warning signs and increasing symptoms of sleepiness, probably reaching a state of fighting off sleep before an accident. There is an accumulating body of evidence to indicate that individuals can detect changes in their levels of sleepiness sufficiently to make a safe decision to stop their task [3-5]. But the problem is, we are not responding to our known state of impairment.

Can people be expected to respond more preventatively to fatigue symptoms, before they become a statistic?

There are limitations when relying on individuals to judge their own level of fatigue and take preventive action. It is also known that performance insight or our ability to self-monitor is impaired as an individual’s fatigue progresses. However like most things in life, practise makes perfect and managing fatigue is no exception.

Managing fatigue is a skill just like learning to surf, playing the guitar or juggling. If we are willing to take the time, make the effort to gain the knowledge, skills and resources with respect to fatigue, we may be better equipped to manage any danger that fatigue will present in our work or personal lives.

Can you expect the community to respond to fatigue in a preventative manner to better manage fatigue?

Some may reflect on this question and respond “you can never get people to take responsibility and take action when it comes to fatigue.” However there is a history where safety initiatives have built enough social capital to underpin their success. Take seat belts for example: the ‘Click, Clack, Front and Back’ campaign. You know a safety initiative has had its effect when your eight-year-old says (as you are pulling out of your driveway), “hang on, I haven’t got my seat belt on”.

What should we expect of others and of ourselves in managing fatigue?

It is important to firstly set our own expectations about responding to fatigue before we can determine a reasonable community response.

If someone was driving home from work following their night shift and they were fighting against sleep, what would you expect them to do? Invariably, the response to this question is… STOP AND TAKE ACTION! Most people don’t hesitate in this expectation of others. However, you might be surprised that the reasonable expectation you have of that person is the same expectation that people would have of you in the same scenario.

What would be your expectation if you had loved ones driving a vehicle on a long car trip and they were experiencing escalating symptoms of fatigue? What advice would you give? It certainly would not be to ignore the symptoms and push through. It might sound more like, “if you experience any symptoms of fatigue… stop, revive, survive.”

So why is it, when it comes to our own personal response to fatigue we are not responding to the early warning signs?

It would appear that we are aligned when it comes to community expectation and fatigue. What we need to work on is the commitment to community action, and the action needs to be shared!

What are the signs of fatigue and when should I take action?

This symptom chart below is a good resource to understand the subtleties of fatigue symptoms and when it is appropriate to respond. The chart lists fatigue symptoms in increasing severity from being fully alert on the left to extremely fatigued on the right.

When a group of people is asked where they expect their colleagues to stop and take action, everyone has the same expectation, stop and take preventative action in the yellow section at ‘A Little Fatigued’. When asked “Why not the orange (Moderately fatigued) section”, people invariably respond, “it’s too late, as you don’t know how close you are to falling asleep.”

Now, remember that same reasonable expectation that you have of another person is the same expectation they have of you. Please share the symptoms chart to start creating a community expectation of responding to prevent fatigue.

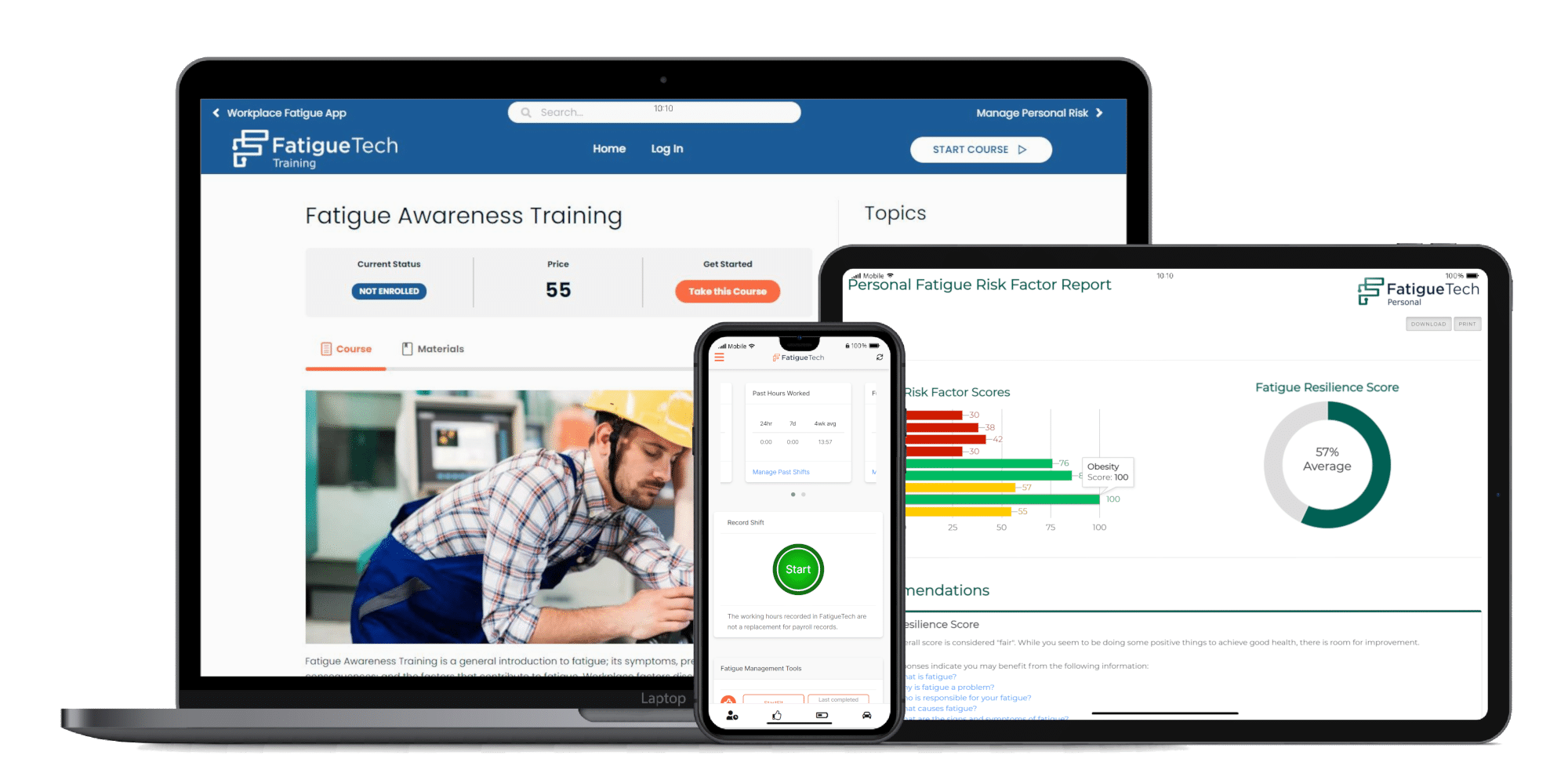

If you would like help with your workplace Fatigue Risk Management Systems, click here for more information.

References:

- Haworth, N., J. Triggs, and E. Grey, Driver fatigue: Concepts, measurement and crash countermeasures. 1988, Monash University: Report No.

CR72. Federal Office of Road Safety: Canberra. . - Council, A.T., National Road Safety Strategy 2011-2020. 2011.

- Lisper, H.O., H. Laurell, and J. van Loon, Relation between time to falling asleep behind the wheel on a closed track and changes in subsidiary reaction time during prolonged driving on a motorway. Ergonomics, 1986. 29(3): p. 445-53.

- Williamson, A., et al., Are drivers aware of sleepiness and increasing crash risk while driving? Accid Anal Prev, 2014. 70:

p. 225-34. - Horne, J.A. and C.V. Burley, We know when we are sleepy: subjective versus objective measurements of moderate sleepiness in healthy adults. Biol Psychol, 2010. 83(3): p. 266-8.