What is Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), and how can a dietitian help?

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is characterised by gastrointestinal symptoms and is only diagnosed after the exclusion of other gastrointestinal diseases, such as coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IBS is diagnosed in approximately 15% of the population but is thought to be higher as diagnosis and treatment are challenging. IBS can significantly impact a person’s quality of life including their work and social life. Triggers of IBS symptoms are highly individual but there is strong research that the use of the low FODMAP diet is effective in up to 70% of IBS patients.

What causes IBS?

There is no known cause of IBS and it is likely to be multifactorial. Some of the mechanisms in the body include:

- Altered gastrointestinal motility

- Visceral hypersensitivity

- Impaired perception and processing of information by the brain

- Low-grade inflammation

- Immune system activation

- Intestinal permeability

- Alterations in the gut microbiota.

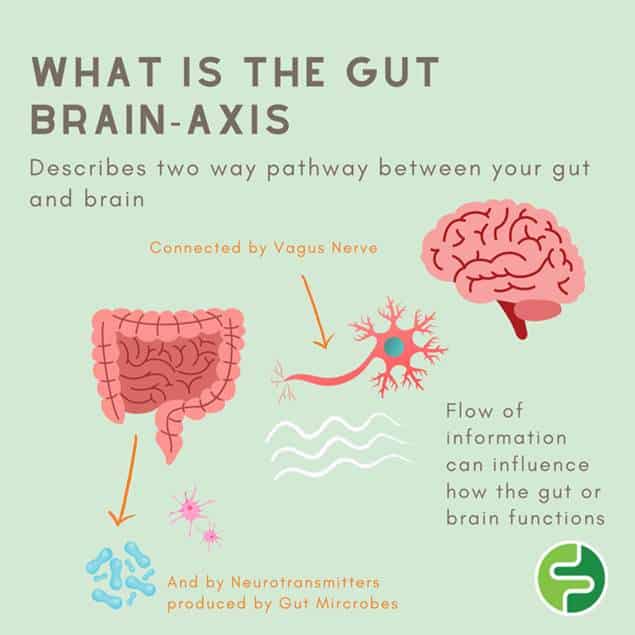

IBS and the gut-brain axis

The ‘gut-brain axis’ refers to the two-way relationship between the gut and the brain. Communication occurs via the vagus nerve and also through chemical messengers known as neurotransmitters some of which are made by the microbes that live in the gut. Neurotransmitters are used in the brain for many functions including memory and regulation of mood. Brain function can affect digestive function and the health of your gut may affect your mental health. This flow of information can influence how the gut or brain functions and may be a contributing factor in IBS. People with IBS have reduced vagus nerve function and altered gut microbes.

Symptoms of (IBS)

Physical

- Lower abdominal pain

- Altered bowel habit (diarrhoea, constipation or a combination)

- Bloating /Distension

- Excessive wind

Psychological (note: stress can also be a trigger for IBS)

- Embarrassment

- Stress

- Fear

- Fatigue from symptoms

How is IBS diagnosed?

IBS should be diagnosed by a medical practitioner (GP or gastroenterologist) using the Rome IV criteria. This criteria includes the frequency of pain related to stool changes and consistency, using the Bristol stool chart to identify the subgroup of IBS, for example hard lumping stools would be IBS-constipation.

It is important that medical professionals complete appropriate testing, as IBS is diagnosed based on exclusion of other conditions and symptoms. Before seeing a dietitian ensure you have spoken with your GP about your symptoms and have appropriate testing done before your appointment.

What are FODMAPs? FODMAP is an acronym that stands for;

Fermentable

Oligo

Disaccharides

Monosaccharides

And

Polyols

Put simply, FODMAPs are carbohydrate foods that due to their small size are either poorly absorbed or not absorbed at all. This causes water to move into the intestines where fermentation occurs generating gas. In people with IBS, this causes pain and symptoms from above due to gut sensitivity or altered motility.

Steps you should take before starting a low FODMAP diet

A low FODMAP diet is very restrictive and should be the last step in improving gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Avoid common dietary triggers: Excess caffeine, fat, alcohol, spicy food, artificial sweeteners

- Manage other triggers such as stress and sleep.

- Trial small frequent meals to reduce load on the gut

- Trial adequate and/or consistent fibre intake

- Stay hydrated by drinking enough water

- Practise mindfulness

- Gentle movement: yoga, walking, cycling.

How a dietitian can support someone trying a low FODMAP diet

- Screen for suitability to commence a low FODMAP diet

- Explain the full process – 3 parts

- Ensure nutritional adequacy

- Gives resources and tips

- Help form a shopping list

- Explains that the restriction phase is a short term trial

- Supports the reintroduction of excluded foods to avoid unnecessary restriction

- Assist in other strategies if no symptom improvement from low FODMAP eating

Look for a Monash FODMAP trained dietitian.

What is the low FODMAP diet?

Firstly, dietitians would prefer if it was named the Low FODMAP process as it is not a long term diet and it is very important it is not followed long term. The three phases are described below. The goal of the process is to learn what your individual triggers are as no two people with IBS are the same, then reintroduce as many foods as possible. Many people cut out foods like garlic or dairy but still experience IBS symptoms. There are many groups of FODMAP foods and if only garlic and dairy are excluded (for example) but symptoms persist, it may be because it is other FODMAP foods or groups that trigger your symptoms.

Phase 1 Low FODMAP Diet trial (2-6 weeks).

Only low FODMAPs foods are eaten.

Phase 2 – FODMAP Reintroduction (8-12 weeks)

If your symptoms have improved this indicates that FODMAPs foods play a role and you can start to systematically reintroduce foods. Foods are introduced with your dietitian’s guidance, based on your history. Each FODMAP subgroup must be introduced separately following a clear protocol provided by your dietitian. If symptoms worsen during the reintroduction of any FODMAP food,remove that FODMAP type from your diet and discuss how to retest with your dietitian.

Phase 3 – FODMAP Personalisation

Personalise your FODMAP diet with a dietitian to ensure your diet is nutritionally adequate. Include well-tolerated foods and restrict poorly tolerated foods to based on your level of tolerance (this can be determined with the support of your dietitian).

What to do if the low FODMAP diet doesn’t work

Firstly, check with your dietitian to ensure you have been avoiding ALL high FODMAPs foods. If you have but your symptoms have not improved, here are some other ways to manage IBS:

- IBS-specific hypnotherapy can be as effective as the low FODMAP diet. E.g. Nerva app

- Stress management

- Gentle movement

- Trial fibre intake- your dietitian can work with you to increase or decrease certain fibres

- You might be referred back to GP for further investigation.

Low FODMAP cooking tips and recipes:

Adding flavour on a low FODMAP diet

- Garlic infused oil

- Spices

- Ginger

- Lemon or lime

- Fresh herbs

- Spring onions – only the green part

Where to find low FODMAP recipes

- Monash FODMAPs app or book

- Online at Monash https://www.monashfodmap.com/recipe/

- https://www.fodmapeveryday.com/recipes/

- Dietitians on Instagram

- Meal delivery services: https://www.dineamic.com.au/

Recipe: Salmon & pumpkin frittata – suitable for low fodmap

6 eggs

1/4 Kent pumpkin

1 cup broccoli heads

1 zucchini

1 large potato

1 cup lactose free milk

1/4 cup Parmesan cheese

2 green parts of a spring onion

Smoked salmon

Garlic-infused olive oil

Salad to serve

Method

1. Preheat oven to 180 degrees fan forced and grease a 20cm x 30cm baking dish

2. Chop the potato and pumpkin

3. Toss in oil & air fry or bake while you prep the rest (20 minutes)

4. Slice salmon & keep in fridge until ready to bake

5. Slice zucchini & green parts of the spring onion

6. Chop broccoli heads

7. Whisk 6 eggs with 1 cup of milk, salt & pepper

8. Add the cheese

9. Combine all ingredients and place in a baking dish

10. Bake for 30-40 minutes or until golden on top.

About the author

Scarlett Gray is a dietitian at Ethos Health, Scarlett has completed the low FODMAP Monash training and works with many clients with IBS or gut-related conditions.

Book with Rowan or Scarlett for assistance with IBS or other gut-related disorders

References

- https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs

- Monash online training: The Low FODMAP Diet for IBS

- Monash resources https://www.monashfodmap.com/ibs-central/

- Drossman, D.A. and W.L. Hasler, Rome IV-Functional GI Disorders: Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology, 2016. 150(6): p. 1257-61.

- El-Salhy, M., et al., The role of diet in the pathogenesis and management of irritable bowel syndrome (Review). Int J Mol Med, 2012. 29(5): p. 723-31.

- Ostgaard, H., et al., Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep, 2012. 5(6): p. 1382-90.

- https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.11.001